https://tessa.substack.com/p/totalitarianism

Why Totalitarianism

A look into history, the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and our souls.

| Tessa Lena | Aug 22 | 29 | 38 |

https://tessa.substack.com/p/totalitarianism

The first part of this story is about my people, their grinder, historical parallels, and my life. The second part of the story is about tricks and the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The pressure is so high, and it’s all moving so fast that the tongue gets numb—but I keep thinking about how the Soviet adults became the way they were—and what we can do about love.

As I was almost ready to post this story, a friend sent an interview with a 94-year-old (non-Soviet) man. Check it out, it’s interesting.

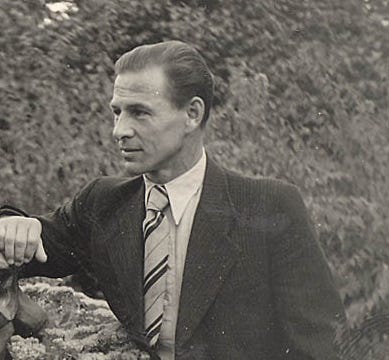

It made me think about my grandfather—whom I think about a lot. From my childhood, I mostly remember the simple things: his unassuming kindness, his toiling in the garden, and the delicious berries he brought me (and apples, and tomatoes that compared to no other tomatoes in the world, and a million other things). I didn’t have the wisdom to ask him about his life enough. Only now I realize how strong he was. When the WWII started, he was a student and a semi-professional athlete. He went through the war. He was resilience. He always took pain and illness stoically, without complaining. Even in his older age, he was athletic and very handsome. I don’t know what he would think of today. His generation was such a mystery, and I long to finally give my love in a proper way.

And now the story.

The emotional trajectory of my people in the USSR has impacted me viscerally. Their trauma—the trauma that I actively resented—made me run away to America. It is strange and ironic that today, I am suddenly seeing the beginning of the movie about psychology whose ending I saw years ago back home—or at least an attempt to play that movie again.

It so happens that as a child, I spent a lot of time around the people from my grandparents’ generation. I looked up to them and simultaneously learned about the world by observing them.

I suppose I’ve always been philosophically inclined—and even as a kid, I was drawn to connecting the dots and analyzing what leads to what. What I observed in the generation of my grandparents was great strength, great resilience, and a general lack of unobstructed happiness. Their marriages, on average, were full of bickering, their lives were about toiling—and their ideology was, “Life is hard.” There were great resilience and selflessness. There was great strength. There was no place and no allowance for individual joy—and not much expectation of it, either.

As a child, I concluded—without using the lofty words that I use today—that the acceptance of martyrdom led to lasting martyrdom.

Many years later, I realized that they’d been played.

My grandparents’ generation’s acceptance of struggle as the default way of thinking about things didn’t come from nowhere. Their lives were ridiculously hard. They were the generation born shortly after the revolution of October 1917. They were raised into the linear and uncompromising Soviet ideology that claimed the absolute superiority of the official, state-formulated “common good” over the selfish good and petty desires of an individual. (A con for the masses, without a doubt—since the party leaders were quite the bourgeoisie.)

Click on the link for the rest.

Skip to the content

Skip to the content